David Gordon by Suzanne Carbonneau ©2002 Suzanne Carbonneau/Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival

David Gordon

David Gordonby Suzanne Carbonneau

©2002 Suzanne Carbonneau/Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival

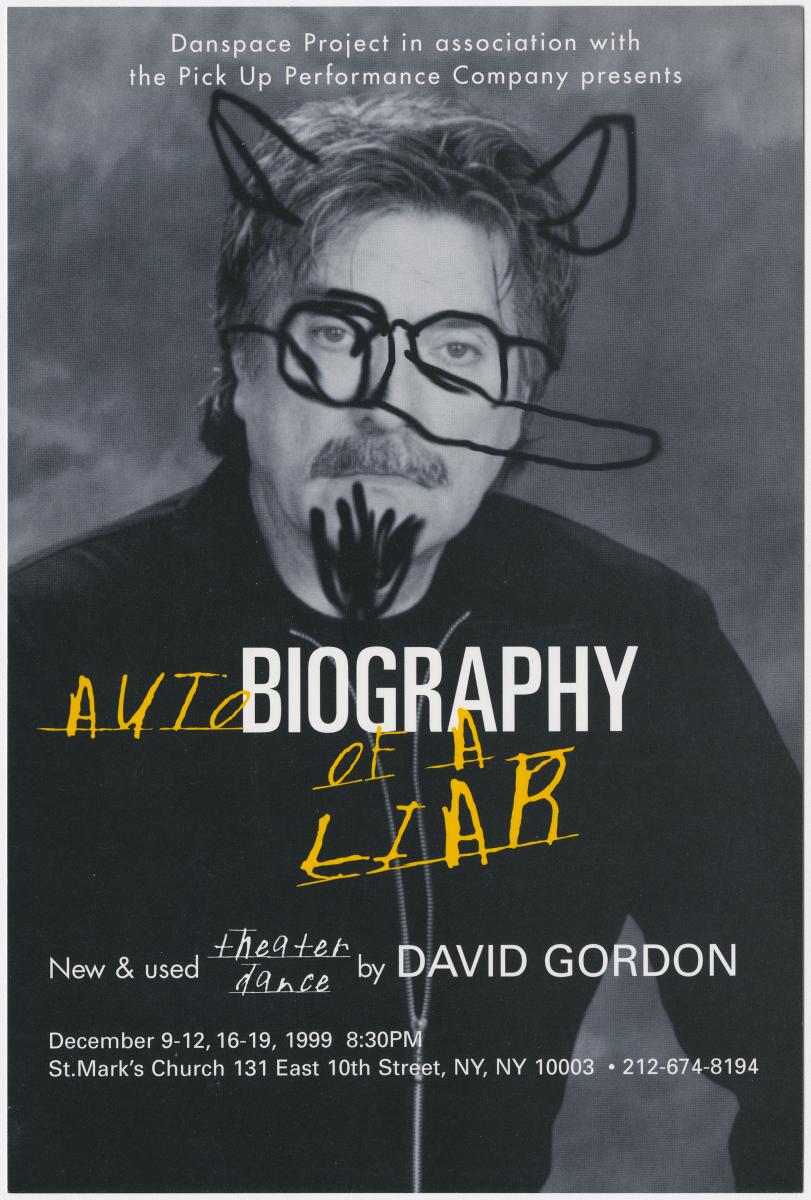

←What do you call an artist who would title a work Autobiography of a Liar?

A postmodernist. (Ba dum.)

But seriously, folks…you would. And not a little to the vexation of the artist himself who declares the terms "postmodern choreography" to be "stakes driven into the heart of a work."

Nevertheless, the artist in question, choreographer/writer/director David Gordon is identified in history books as a founder of what is now generally called postmodernism in dance. And whether or not you accept this description of his achievement, there is no question that Gordon's presence in the field has irrevocably and permanently expanded what we conceive dance to be. A member of the Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union, the choreographic and improvisatory collectives that revolutionized modern dance by stripping it of the Romanticism and Expressionism of its founders, Gordon has remained in the succeeding forty years one of the most consistently experimental and original artists working with movement. For despite critical acclaim and an assured place in history, Gordon has yet to show any signs of resting on his laurels. Today, he remains as defiantly maverick—and important—as he was when he shared stages in Greenwich Village in the 1960s with Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and Steve Paxton.

Gordon created Autobiography of a Liar in 1999, and, in addition to being a collection of personal and creative vignettes, the work is also a compendium of the concerns that he has been examining over the course of his career. The title is a joke, of course, but is, at the same time, immensely serious in its questioning of the idea of perception as unreliable, of memory as fallible, and of truth as ultimately unknowable. It is a theme he has returned to again and again. Yet, even as he is aware of his fool's errand, Gordon will go ahead and make the attempt at finding truth – or rather, competing truths – all the while openly (eagerly!) exposing the rickety and ultimately illusionary nature of the enterprise. The glue that invariably holds all of these contradictions together is Gordon's keen wit. Exhibit A: Gordon describes Autobiography of a Liar as "half remembered half truths about dances made another time in another life accommodating the talents of performers I was in love with and remade for the talents of performers I hope to be in love with now." And many such passages of Gordon's works have more in common with Abbott and Costello and their "Who's on first?" routine than they do anything choreographed by Martha Graham.

Such verbal dexterity is matched by a physical language whose virtuosity is also concerned with punning, allusion, about-faces, and multiple meanings, and these twinned and twined disciplines are the hallmarks of his work. For Gordon, all language implies action. Interested in the ways that the interaction of words and movement increase the possibilities for complicating and layering meaning, he ricochets between the scrupulously literal and the fancifully symbolic meanings of both words and actions, and is most happy, it seems, when these things exist simultaneously.

This idea of revealing each work's philosophical and structural scaffolding is endemic to Gordon. Most of the work he has made since the 1970s has dealt with the idea of performance as an illusion that is created by real people. And like Penn and Teller who purposefully betray the cardinal rule of professional magicians by revealing to their audiences how their tricks are done, Gordon also exposes how his work is constructed by mixing autobiography and fiction, by moving back and forth between performer-as-performer and performer-as-person, by acknowledging the false authority of the creator, by foregrounding the artificiality and manipulation of the theater, by revealing process, by breaking the theatrical "fourth wall," and by inserting matter-of-factness into the most magical theatrical moments.

In fact, his works are backstage musicals taken to their ultimate conclusion. The incorporation of his family (his wife, the luminous dancer and actor Valda Setterfield, and his son, playwright and director Ain Gordon) as performers and co-creators only makes things more devilishly tricky as what is real and what is not in the relationships we see on stage come to seem hopelessly entangled. The Gordons's madcap and heartrending Obie-winning The Family Business(1994), for example, is about a plumbing concern but it's also about this family business and this family's business. (Gordon plays an old mustachioed woman who is really Gordon who is also his aunt, while Ain is a father and his son who aspires to be a playwright who will write the play that is actually being performed now, and Setterfield is the mother and…you get the picture.) Following who's who and what's what at any given moment of this work makes that infernally labyrinthine Abbott and Costello routine seem like a Dick and Jane reader.

Because Gordon has used language in performance virtually from the beginning of his career, to call the work "choreography" misses what is essential to its nature. (Hence, Gordon's annoyance with the term. Up until recently, he preferred to call his work "work," and to say that he "constructed" it.) In fact, most of the standard categories for differentiating performance cannot begin to suggest what it is that Gordon does. These characterizations exist only for the intellectual convenience of those who need familiar archetypes with which to try to come to terms with artistic achievement—even experimental achievement. But these constructs are inadequate, if not outright dishonest, as descriptions of his work. Gordon is not interested in conforming to ideas about what he should be doing, or to fit in with what other artists have done or are doing; rather, his interests lie in expanding ideas about what performance can be. And, after all these years, his impatience with the whole business is understandable.

During the last decade, Gordon's work has been most often categorized as theater – although his original work is not any closer to the traditional notion of drama than it was dance. For if these works are "plays," they would have to be described as profoundly choreographed. In these works, everything moves—sets, props, performers. In fact, they are so thoroughly conceived from the standpoint of movement that, even with their fully fleshed-out texts, every moment is dancerly. You'd be hard-pressed to pick out "dance" sections as they exist as interludes in traditional plays; rather, it's all dance, even if there's not a recognizable dance "step" in sight. Even the text, which is conceived from a rhythmic as well as a narrative standpoint, contributes to the sense of propulsive action. This is a singular achievement: no other movement artist has achieved this level of integration in the theater as writer, director, and choreographer.

With this theatrical work, Gordon has finally embraced the use of the term "choreography" to describe his movement contribution to these integrated performances. For the term is no longer a limitation, but a more apt description than "blocking" or "staging" of how it is that Gordon conceives these works, alongside his writing and directing. Gordon has also been in the spotlight recently as the director and writer of "PAST Forward" (2000), White Oak's hugely successful Judson Dance Theater revival program that was instigated by Mikhail Baryshnikov. And if this canonization of an American avant-garde revolutionary by a Russian ballet dancer conjures visions of the Disneyfication of the Impressionists, rest assured. Somehow, one knows that Gordon's work is undoubtedly too uncompromising, too witty, too prickly, too analytic, too complex—in other words, too damn smart—to succumb to mass marketing. And that, of course, has always been the mark of genius.